Modern Psychology & Caim

Before giving the teaching on walking the caim, it will be useful to understand how modern psychology intersects with the ancient caim teachings. As a psychiatric technician at our regional medical facility, Warren General Hospital, I conduct therapy groups in our acute care inpatient mental health unit. I developed a therapy group based on the teachings of the sacred circle, whose ancient principles form the core of the contemporary therapy model known as Whole Health Recovery. Whereas Western medicine has long compartmentalized physical, mental, and spiritual health, treating them as separate, distinct, and unrelated systems, Whole Health Recovery treats them as different but related aspects of the whole self. When one becomes physically ill, the illness does not exist in isolation but affects our whole being. When we become emotionally drained, we find it difficult to reason, and we may find our spiritual relationships shaken or shattered depending on the severity of the illness. In other words, when we get sick, our whole self is sick, and our recovery must follow the same course. We treat symptoms to alleviate suffering, but recovery is more than minimizing or eliminating the cause of our pain. We must facilitate a healthy way of life that encourages the mind, heart, body, and spirit to heal the self, thus restoring harmony and balance. This approach allows us to treat a person rather than a disease and to see the broader implications of illness. We may achieve this holistic healing through the Caim.

Remember that the Irish Gaelic word Caim means “Protection” or “Sanctuary” and is described as a magical circle often divided into four quadrants. Carl Jung, the founder of Analytical Psychology, considered the “Quaternity” a universal archetype. He believed that individuation, the process in which a person achieves unity and balance through a synthesis of consciousness and the unconscious, is a spiritual journey expressed by sacred quaternities:

“The quaternity is an archetype of almost universal occurrence. It forms the logical basis for any whole judgment. If one wishes to pass such a judgment, it must have this fourfold aspect. For instance, if you want to describe the horizon as a whole, you name the four quarters of heaven… There are always four elements, four prime qualities, four colors, four castes, four ways of spiritual development, etc. So, too, there are four aspects of psychological orientation… In order to orient ourselves, we must have a function which ascertains that something is there (sensation); a second function which establishes what it is (thinking); a third function which states whether it suits us or not, whether we wish to accept it or no (feeling), and a fourth function which indicates where it came from and where it is going (intuition)…The ideal completeness is the circle or sphere, but its natural minimal division is a quaternity.”1

Quaternities teach us about natural cycles. In the first article I published on the Caim, I discussed several of these cycles, including the four seasons, phases of the moon, hills of life, and so on. When used for meditation, the Caim brings harmony and balance by attuning us to each of these natural cycles and, therefore, to the Universe as a whole. When used for therapy, it fosters Whole Health Recovery.

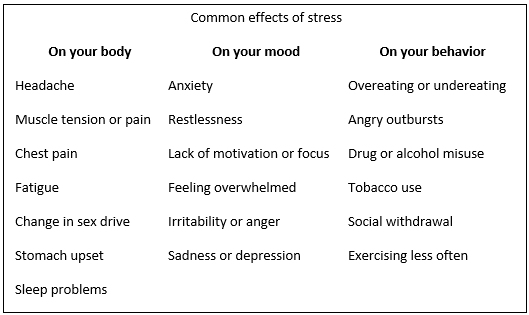

Let’s look at illness from the point of view of our whole health. Illness does not act in isolation but affects the mind, body, and soul. Consider stress, which research has linked to hypertension, heart disease, obesity, and diabetes.2

By way of example, I went through a divorce several years ago, and when my ex-wife and I decided to end our marriage, I vomited every meal for an entire week. My father took me to a local restaurant, where I took a few bites of fish filet and ran from the restaurant to purge outside. What happened? A profoundly emotional event affected me physically. I didn’t sleep well, couldn’t think straight, and ruminated on my marriage, custody battle, and financial situation. I felt disconnected from anything spiritual. I was in crisis. Another example, which we all share, is grieving. Five years ago, I lost a good friend. Justin was thirty-seven years old and suffered an aneurysm. I grew up with him and his brother, and their mother was like a second mom to me. Justin’s loss sent me into a depression, which lasted months. I have counseled many people who lost the will to live after losing their spouse. They endure mental illness and sometimes become physically ill, though testing reveals nothing pathologically wrong with them. Moreover, they are angry at God. Spiritual sickness is often a byproduct of grieving. To make matters worse, well-meaning family members push them to “move on,” not understanding that the grieving process takes at least three years in a healthy individual.

Both of the above situations are rooted in emotional responses to profound loss. Recovery is aided by talk therapy, pharmaceuticals or herbal remedies if needed, and time; but what about emotional reactions to irrational thoughts? We evolved to automatically interpret the sensory information we receive, allowing us to predict the potential outcomes of situations and thus increasing our chance of survival, but we sometimes make the wrong assumptions. Our personal history, especially trauma, influences our thoughts and may lead us to false conclusions. When we act on those conclusions, we often injure ourselves or worsen our situation. CBT, or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, addresses this process.3

We can readily perceive the model’s cyclical relationship to the Caim. An event triggers an automatic thought, i.e., we instantly form an assumption based on our limited information. This assumption is informed by our trauma history, our core beliefs about ourself and about reality, and by any unhealthy thinking patterns (cognitive distortions) we engage. Common cognitive distortions include:4

- Magnification and Minimization: Exaggerating or minimizing the importance of events. One might believe their achievements are unimportant or their mistakes are excessively important.

- Catastrophizing: Seeing only the worst possible outcomes of a situation.

- Over-generalization: Making broad interpretations from a single event. “I felt awkward during my first job interview. I am always so awkward.”

- Magical thinking: The belief that actions will influence unrelated situations. “I am a good person—Bad things shouldn’t happen to me.”

- Personalization: The belief that one is responsible for events outside of their own control. “My mother is always upset. It must be because I have not done enough to help her.”

- Jumping to conclusions: Interpreting the meaning of a situation with little or no evidence.

- Mind reading: Interpreting the thoughts and beliefs of others without adequate evidence. “She wouldn’t go on a date with me. She probably thinks I’m ugly.”

- Fortune telling: Expecting a situation to turn out badly without adequate evidence.

- Emotional reasoning: The assumption that emotions reflect the way things really are. “I feel like a bad friend, therefore I must be a bad friend.”

- Disqualifying the positive: Recognizing only the negative aspects of a situation while ignoring the positive. One might receive many compliments on an evaluation but focus on a single piece of criticism.

- “Should” statements: The belief that things always need to be a certain way. “I should never feel sad.”

- All-or-nothing thinking: Thinking in absolutes such as “always”, “never”, or “every”. “I never do a good job on my work.”

Our initial assumption or automatic thought is reinforced and validated by our emotional response. With emotional power invested, consciously or unconsciously, the thought grows into a belief. We become certain that our initial assumption about the situation is correct. The more this belief reinforces one of our core beliefs (those deeply rooted concepts about the nature of reality, which, rational or irrational, form the crux of our worldview), the more confident we are of its validity. This is called confirmation bias. We tend to gravitate toward ideas that reinforce our preconceived notions of reality. The belief we hold about the triggering event is emotionally reinforced again but at a higher energy level. If we felt afraid at the start, we are now terrified; if angry, we feel enraged. When we reach the tipping point, our stress compels us to act, and we reach the behavior stage of the model. If our initial assumption came from a cognitive distortion, and our emotional response was negatively charged, we will engage in negative behavior, in turn yielding negative consequences, each of which trigger (depicted as lightning bolts in the illustration above) new automatic thoughts and emotional reactions. One bad day and our lives seemingly spiral out of control.

Consider the following example: “Julia” is up for a promotion at work. She has been employed at the company for five years, displayed good work habits, punctuality, and an amicable relationship with the staff. Julia is in competition with three other employees for a promotion, which her boss awards to one of her coworkers. Julia experiences an automatic thought that her boss doesn’t like her. She is jumping to conclusions by mind reading, having no evidence, but nevertheless feels angry. The more she ruminates on the lost promotion, the more her anger reinforces her cognitive distortion until it becomes a belief. The belief enrages her, strengthening her initial emotional response. Eventually, convinced she lost the promotion simply because the boss doesn’t like her, Julia storms into her boss’s office and quits her job after giving her boss a piece of her mind. Consequently, she has lost her income, benefits, vacation time, etc.… Depending on her disposition, she may or may not later come to realize that there were other plausible causes for not receiving the promotion.

Another example: John receives a text from his wife every day at lunch, inquiring about his day and saying she loves him. One day, while John is at work, his wife fails to text. He waits until the end of his lunch break and then texts her, asking if she is alright. John’s automatic thought is that something is wrong, and his emotional response is fear, which quickly ramps up to anxiety by the end of his break. His assumption that something is wrong is validated when his wife fails to answer his text. His anxiety reinforces the assumption until he believes his wife is ill, injured, or dead, or any number of negative scenarios. Perhaps one of them had an affair at some point, and John’s automatic thought is that his wife is cheating. Whatever the belief, it becomes strengthened by the emotional response and, in turn, ramps up the anxiety into a panic. John leaves work and drives home, incurring disciplinary action from his boss. If this has happened before, he may lose his job. John catastrophized, fearing the worst possible outcome, and acted without rational evidence to justify his initial assumption.

How do we break this cycle? The first step is achieved by practicing mindfulness. Our goal is to remain in the present moment, experiencing our thoughts and feelings without passing judgment over them. In this way, we may learn to recognize our cognitive distortions as they occur. Meditation is beneficial for developing mindfulness, and as Ovates, we have several techniques at our disposal. The most effective is Light-Body. We begin by inhaling through the nose, conscious of the intake of oxygen into our lungs, and exhaling out through our mouth, observing the rising and falling of our chest, the feeling of our lungs expanding and contracting. Using visualization (this can also be accomplished through guided imagery), allow bright white light to rise through the earth, and up through the soles of our feet, or whichever body parts are in direct contact with the ground, floor, etc. As the light courses upward, allow each body part to relax, taking in a deep breath through the nose, and exhaling tension through the mouth.

If intrusive thoughts enter your mind during this practice, acknowledge them in a non-judgmental way, saying to yourself, “I am thinking,” and then letting them go. Eventually, as you practice Light-Body, the instances of intrusive thoughts will decrease. It is helpful when faced with anxiety to enter sacred time. Allow yourself to breathe. How often, when faced with stress, do we forget to breathe? We clam up, hold our breath, and wait for the worst to happen. Breathe, and allow the Light Body to do its work in sacred time. Once this is accomplished, allow your attention to drift over the triggering event, not focusing or fixating on it but surveying from above, like a hawk circling a field. Now, from a place of safety and security inside the Light Body, consider your initial assumption, the automatic thought that popped instantly to mind. Does it conform to one of the cognitive distortions listed above? It’s vital this is done in a non-judgmental way. Don’t condemn yourself. Everyone experiences cognitive distortions.

If we learn to recognize our cognitive distortions as they occur in our thoughts in real-time, we are then able to stop ourselves from emotionally escalating by practicing a technique called Reality Testing. Ask yourself, “Do I have objective evidence to validate my assumption?” The key word here is objective, evidence based on established facts. There are several techniques you may use. In the double-standard method, ask yourself, “If a close friend faced an identical circumstance, would I suggest the same thought or response for them?” A similar approach is the survey method. Ask yourself, “Would others agree that my initial thought is valid?” If the answer to either of these questions is no, you may need to reconsider your response to the triggering event. In the shades-of-gray technique, we evaluate our response to determine if we are engaging in black-or-white thinking. Life is rarely 0 or 100 percent but generally falls somewhere between. If our response to the triggering event is at the extreme end of the spectrum, we are likely experiencing a cognitive distortion. Likewise, we need to evaluate our terminology. If our response to a perceived failure is to say, “I’m just an idiot,” we need to define the term “idiot.” The idea behind this exercise is to recognize all-or-nothing thinking. You are not an idiot. You are a human being who experiences successes and failures. Forgive yourself for being imperfect.

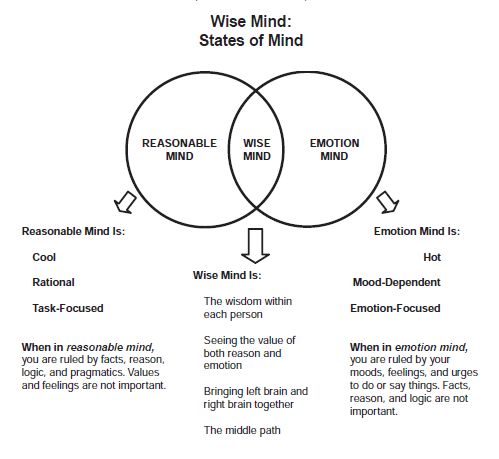

Once we have identified a cognitive distortion, having subjected it to reality testing, we must search for an alternative narrative to explain and cope with the triggering event. Cognitive restructuring teaches us to change the way we think. Ideally, we need a healthy balance between reason-centered thinking and emotional response. As human beings, we are thinking and feeling creatures. Both are essential to our survival. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), a CBT-based therapy specializing in psycho-social aspects of mental health disorders, advances the concept of Wise Mind, seeking a balance between rational and emotional states of mind and incorporating both in the decision-making process.5

In Wise Mind, we perceive alternative narratives. Julia’s boss may have passed her over for the promotion because someone had more seniority than she did or was better qualified for the specific position. John’s wife may have taken a long nap, or her cell was unavailable or inoperable, or she was busy and lost track of time. Instead of concluding that our best friend is mad at us because they invited someone else to see a movie, consider the alternative narrative: My best friend loves me, but they are allowed to have other friends and share their time with whomever they choose. These techniques and many others are employed by therapists in counseling sessions every day. All this information is available on the internet, and there are several self-help guides, but if cognitive distortions are impacting your ability to function in daily life, damaging relationships, or affecting work, it may be time to seek professional help.

Having examined the natural cycles expressed as quaternities in the Caim and having given a therapeutic rationale for Whole Health Recovery facilitated by the Caim, I will now publish the third and final article in the series, explaining how the Caim may be used in spiritual practice to promote health, harmony, and balance in one’s life.

Footnotes

- Carl G. Jung, Psychology and Religion: East and West, 2nd ed., vol. 11 in Collected Works of Carl G. Jung, trans. by R. F. C. Hull (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 165-198.

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress-symptoms/art-20050987

- https://www.therapistaid.com/therapy-worksheet/cognitive-behavioral-model

- Ibid.

- https://dbtlifestyle.com/2018/10/20/mindfulness-worksheet-exercises-wise-mind/